|

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Bikes

Custom Bikes

Individual

Racing Bikes AJP

AJS

Aprilia

Ariel

Avinton / Wakan

Bajaj

Benelli

Beta

Bimota

BMW

Brough Superior

BRP Cam-Am

BSA

Buell / EBR

Bultaco

Cagiva

Campagna

CCM

CF Moto

Combat Motors

Derbi

Deus

Ducati

Excelsior

GASGAS

Ghezzi Brian

Gilera

GIMA

Harley Davidson

Hero

Highland

Honda

Horex

Husaberg

Husqvarna

Hyosung

Indian

Jawa

Kawasaki

KTM

KYMCO

Laverda

Lazareth

Magni

Maico

Mash

Matchless

Mondial

Moto Guzzi

Moto Morini

MV Agusta

MZ / MuZ

NCR

Norton

NSU

Paton

Peugeot

Piaggio

Revival Cycles

Roland Sands

Royal Enfield

Sachs

Sherco

Sunbeam

Suzuki

SWM

SYM

Triumph

TVS

Ural

Velocette

Vespa

Victory

Vincent

VOR

Voxan

Vyrus

Walt Siegl

Walz

Wrenchmonkees

Wunderlich

XTR / Radical

Yamaha

Zero

Video

Technical

Complete Manufacturer List

|

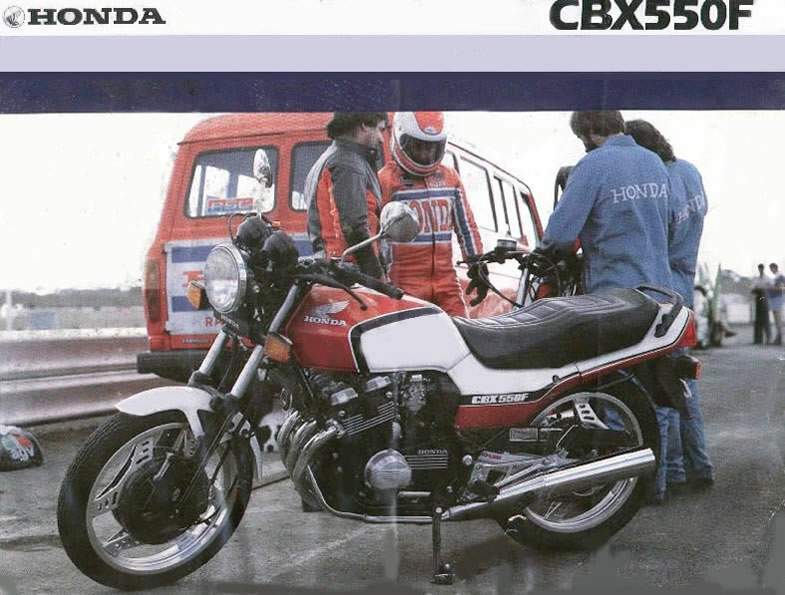

Honda CBX 550F

The Honda CBX550F is a four-stroke, in line four cylinder, sport tourer

motorcycle produced from 1982 to 1986 by the Honda Motor Company. The CBX550F II

is identical apart from the addition of a half-fairing.  THE GROUND EFFECT CRUISER Honda's CBX550 has no conflict of roles: it was built from the ground upi to be a sports bike. Dave Calderwood indulges in a little TT-mania... a// in the course of duty as a tester, of course was now, at last, okay to reflect upon a mad day. Occasionally, all hell breaks i loose on Bike's normally laidback organisation (huh!) and usually it's when j there's a tight deadline to be met plus some other fantastically attractive incentive. Add in the Isle of Man TT week and, boy, you've gotta total freak out. To make sure that the Honda CBX550 was here, between my legs heading up to Heysham to embark aboard the midnight boat, was a masterpiece of careful; manipulation — not too obvious so the others would realise they were being edged away from the CBX but enough to deliver it at 9am to Mike the Designer's home. Back to my garage and load up a GPz750 and XT550 onto the works trailer, sling my

TT stuff into the boot of the towing car and

discover that the over-trousers of my most waterproof riding suit are back in

the office. Definitely can't go to the Isle of Man without those... a little

later, JR arrives with the suit and asks for the photos of the feature I'd

written ... jeez! If I'd left without handing those over there definitely

would've been trouble. At last, an hour behind schedule and still with no

breakfast other than acrid coffee inside me, I'm into the car, off round the

South Circular and up the M1. Exit at the Nuneaton turnoff and a further 20-odd

miles to MIRA where Roland Brown is waiting with the CBX . .. relief. We did our

usual tests on all three bikes, getting very worried at the high speed antics of

the XT550 on its trail bike tyres and a bit disappointed with a maximum of

118mph from the CBX. Finally, just after 2pm and with storm clouds darkening the

sky (Typical! It's TT-time for sure), I pulled on the oversuit and headed

northwards across the Midlands for the M6, leaving Roland to have his first

outing driving the works car and too-wide trailer. At least the radio works . .

.

The glass fibre fairing fitted to the CBX is

securely mounted with a similar rigid structure of tubes to that employed on its

bigger 900F2 and CBX1000 stablemates. Fortunately, it's a lot smaller than those

two bulky items, being only a couple of inches out from either side of the

instruments and widening to encompass the petrol tank. The flip-up edge to the

tinted screen ensures that just enough windblast is tipped over your head to

make ton-up cruising totally effortless (apart, that is, from the nagging worry

about the Old Bill: 'Blimey, I can't get away with this speed all the way up the

M6I). The dual seat is plenty big enough for two though, as seems fashionable now, the footrests are mounted high to clear the silencers and consequently a passenger sits scrumped up. A rubber covered grab rail will comfort them a bit, I guess. A knob inside the fairing adjusts the headlamp beam without recourse to tools and it's a powerful though not stunning illuminator. Rear lamp has two bulbs, useful when one blows at midnight on a motorway miles from anywhere. The footrests, too, are mounted well back and high — as much to ensure good ground clearance as give the right leaning forward riding stance. For this is one motorcycle that's slung low. Seat height is a mere 29 inches when measured without a rider on board. Add 1601b of beer gut and it compresses a bit more, naturally. Sitting astride the CBX with both feet flat on the deck and knees bent, you instantly realise just how small and close to the ground this CBX is. It's as unlike its six-cylinder name-sharer in this respect as it could possibly be. It's also short with a wheelbase of just under 55 inches making the whole package quick to respond to rider input. In other words, when you're halfway round the 32nd Milestone on the TT circuit and you've just realised it wasn't where you thought you were, instead of blindly panicking and stuffing the marker posts on the other side of the road you can lift the bike upright, snatch on the brakes and lay it down again. Or something like that. Fortunately, these good handling traits make it easier to get your line right in the first place: I've never before got the Gooseneck (an uphill sharp right with a permanent audience) so perfect as on the CBX, flat in second and with road to spare.

The 550 is basically a hot version of a CBX400

available only (so far) in Japan. An amazing 62 horses can be wrung out at

10,000rpm, so Honda claim, which in a bike weighing 433lb with a gallon of fuel

gives a power to weight ratio better than most 750s. It's even ahead of that

King of the Street Racers, Yamaha's RD350LC. With max power coming just 1200rpm

short of the redline, and with max torque also set pretty high in the rev band

you'd be forgiven for expecting the CBX to be as peaky and unpredictable in its

delivery as a Manx pub on a Sunday. True, most of the real stomp comes above six

grand — there's a bit of a lull at five grand which needs steaming through — but

it'll also chug along at tickover and accelerate in top with hardly a trace of

transmission snatch. It won't respond with this load as lively as it does when

it's on full honk but the fact that it's possible to cruise steadily without

recourse to all of the six well-spaced ratios is reassuring. If you really hang onto the throttle and keep a careful eye on the tacho — plus coordinated limbs around gearlever and clutch — then the CBX'II go in a way that has even the average rider thinking about going proddy racing. Certain clubs have events regulated to Formula Two capacities (600cc four-strokes v 350cc two-strokes) and imagine a race full of GPz550s, CBXs, Ducati Pantah 600s and RD350LCs .. . imagine the close dices, the carnage, the happy spare parts dealers. This kind of extreme behaviour doesn't come for free though. To keep down the weight of the motor and size of the crank-cases, Honda have opted for a sump of only 2.6 pints with a six row oil cooler neatly mounted below the fairing giving much needed assistance. Service intervals call for an oil change every 2000 miles (admittedly cheap with only this volume) and a new filter every 4000. Other items are relatively easy: ignition is fully electronic including the advance/retard, carbs are CVs which basically means Don't Touch except for balancing throttle slides, air filter is easily got at, and tappet clearance is by good ol' threaded adjuster.

These require inspection every 4000, according to

the manual, and replace the bucket and shims of the original CBX-6. Apparently,

the Japs intended dealers to operate an exchange service on shims— not just for

bikes they serviced but also to DIYers — but that just hasn't happened widely

enough. Either the dealers didn't get the mesage or they're being just plain

unscrupulous in selling new (and not cheap) shims each time adjustment is

needed.

That's similar to Ridden Hard figures for the GPz550

and also the RD350LC. Trouble is, sitting behind that fairing you just don't

suffer the same fatigue as on those other bikes so you're tempted to go

everywhere flat through the gears. There's a certain amount of vibration finding

its way through the 'bars even though the solid knobs at each end are supposed

to damp tingles out: engine mounts are solid to the frame — in the interests of

rigidity, I suspect, on such a pure sports bike. Honda achieve their Rising Rate monoshock rear suspension completely dif-fently from Kawasaki's Uni-Trak. Whereas Uni-Trak squeezes a conventional coil spring shock absorber from both ends via two independent systems of levers and rocker arms, on the CBX Pro-Link a pair of arms from each side of the extruded alloy swing arm operate onto the bottom of the shock only, with supporting connecting rods to the frame. The top of the shock is fixed to the frame top tube behind the petrol tank. No adjustment for damping force is provided, unlike with Uni-Trak, and to alter 'spring preload' there's an air compartment within the shock to back up the main coil spring (shrouded so it looks as though it's an air shock alone). Honda's system doesn't have as much range as Uni-Trak in increasing the stiffness of the suspension under compression so you have either to pump up the shock to cope with the worst bottoming and therefore suffer over ripples, or go for a compromise. While it doesn't offer as good suspension as Uni-Trak, it is still pretty damn impressive though the test bike would lose a couple of psi overnight. It's easier to adjust preload than on many monoshocks and it's possible to clip on an S&W air pump without removing the right sidepanel. Which is just as well: production line economies have made items such as plastic sidepanels extremely fragile and tacky. Our CBX test bike came with Quickly Detachable locating knobs — unlike the GPz550 which at least has a coupla metal screws as well and I've seen another CBX on the road with the same sidepanel missing, presumed squashed. For sure though, the wheels ain't QD. Wheel design is fine — attractive and rigid rolled alloy items which are a progression of the old Comstars but the enclosed disc brakes are a hangover from another age. Quite responsibly, Honda R&D obviously set more than one team working on the problem of disc brake lag in the wet when it was a serious worry for European riders in the seventies. The solution which has now been adopted by most manufacturers including Honda on other models is simple: add metal content to the disc pads. Any engineer will tell you that the simplest solution to a mechanical problem is always best. Honda's other R&D team tackled it by trying to protect pads and rotors from getting wet in the first place, an idea mooted by lots of people originally but one which was not easy to do because of the heat generated. But since they'd invented such a device Honda decided to add it as one more USP (Unique Selling Point as the marketing men say). Pity. It's not just the time it takes to remove the wheel though that's bad enough. It took me two hours to remove and replace the front wheel when all I wanted to do was inspect the construction of the brake and find out how it worked. Even trained Honda mechanics can only get it down to one hour 20 minutes so it wasn't just my hamfisted wrenching. And contrary to what you might have read elsewhere (why?) the tubeless tyres fitted don't make punctures any less likely, just less dangerous when they do happen since deflation is slower. No, the only point in fitting such a brake would be if it offered improved braking over currently available set-ups — and it doesn't. In fact, under repeated heavy braking at the test track the front unit faded until it was possible to pull the lever back to the bar. Such ferocious stopping isn't commonplace on the road, of course, but more telling was comparing it with the GPz750 tested at the same session. That bike, weighing 531b more and travelling at 126mph, stopped in a shorter distance than the CBX from 118mph. Same rider, same conditions.

All this isn't to say it's a bad brake: under normal

road use and even near panic crash stops when confronted with a TT wally, it

coped adequately. It's just that there's an easier solution — metal pads.

Unusually for a Japanese middleweight, the CBX often

surprises you with 1) how fast you're travelling and 2) how far you've travelled.

Number 2 happens most often when the petrol tank goes onto reserve, a reasonable

3/4-gallon, at around 100-115 miles. That's not enough for such a bike and it's

irritating to have to stop so often if you've real distance to cover. But

otherwise the CBX comes across as a well thought-out motorcycle leaving would-be

riders in only one quan-dry: CBX or GPz or RD350LC? Assuming you're a

four-stroke fan and it's a straight choice between GPz or CBX, the Honda's

excellent fairing and small size would win me over. However, it's easy enough to

fit a fairing and then the GPz's slightly better rear suspension, bucket and

shim tappet adjustment and 'ordinary' disc brakes would take the advantage.

Heck, it's just too close to make judgements over trivia such as colour schemes

or switchgear an' all that stuff. I guess we'll just have to envy those in a

position to go for either.

|

|

|

Any corrections or more information on these motorcycles will be kindly appreciated. |